Farm Typology And Sustainable Agriculture: Does Size Matter?

The goal of sustainable agriculture is to encounter gild'south nutrient and textile needs in the present without compromising the power of future generations to meet their ain needs.

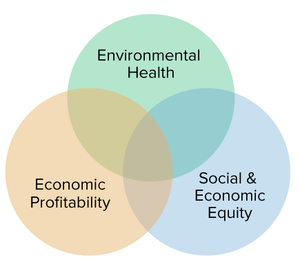

Practitioners of sustainable agriculture seek to integrate three main objectives into their work: a healthy environs, economical profitability, and social and economical disinterestedness. Every person involved in the food system—growers, food processors, distributors, retailers, consumers, and waste matter managers—can play a role in ensuring a sustainable agricultural system.

In that location are many practices commonly used by people working in sustainable agriculture and sustainable nutrient systems. Growers may use methods to promote soil health, minimize water utilize, and lower pollution levels on the farm. Consumers and retailers concerned with sustainability tin look for "values-based" foods that are grown using methods promoting farmworker wellbeing, that are environmentally friendly, or that strengthen the local economy. And researchers in sustainable agriculture frequently cantankerous disciplinary lines with their work: combining biology, economics, engineering, chemistry, community development, and many others. However, sustainable agronomics is more than than a drove of practices. Information technology is also process of negotiation: a push and pull between the sometimes competing interests of an individual farmer or of people in a community every bit they piece of work to solve circuitous issues virtually how we grow our food and fiber.

Topics in sustainable agriculture

- Addressing Food Insecurity

- Agritourism

- Agroforestry

- Biofuels

- Conservation Tillage

- Controlled Environs Agriculture (CEA)

- Cooperatives

- Embrace Crops

- Dairy Waste Management

- Straight Marketing

- Free energy Efficiency & Conservation

- Food and Agricultural Employment

- Food Labeling/Certifications

- Food Waste material Management

- Genetically Modified Crops

- Global Sustainable Sourcing of Commodities

- Institutional Sustainable Food Procurement

- Biologically Integrated Farming Systems

- Integrated Pest Management (IPM)

- Nutrition & Food Systems Educational activity

- Organic Farming

- Precision Agriculture (SSM)

- Soil Nutrient Management

- Postharvest Management Practices

- Technological Innovation in Agriculture

- Urban Agriculture

- Value-Based Supply Chains

- Water Utilize Efficiency

- H2o Quality Management

- Zero-Emissions Freight Ship

Directory of UC Programs in Sustainable Agronomics

The UC Programs | Sustainable Agriculture and Food Systems directory is a catalog of UC'south programmatic activities in sustainable agriculture and food systems. The directory can be searched and sorted past activities and topic areas.

The Philosophy & Practices of Sustainable Agriculture

- Background

-

Agriculture has inverse dramatically, especially since the end of World State of war II. Food and cobweb productivity soared due to new technologies, mechanization, increased chemic utilize, specialization and authorities policies that favored maximizing production. These changes allowed fewer farmers with reduced labor demands to produce the majority of the food and fiber in the U.S.

Although these changes have had many positive effects and reduced many risks in farming, at that place take also been significant costs. Prominent among these are topsoil depletion, groundwater contamination, the decline of family farms, continued fail of the living and working conditions for farm laborers, increasing costs of production, and the disintegration of economical and social conditions in rural communities.Potential Costs of Modernistic Agricultural Techniques

Topsoil

Depletion

Groundwater

Contamination

Degradation of

Rural Communities

Poor Weather

For Farmworkers

Increased Production

CostsA growing movement has emerged during the by two decades to question the role of the agricultural institution in promoting practices that contribute to these social problems. Today this motility for sustainable agriculture is garnering increasing support and acceptance within mainstream agriculture. Not merely does sustainable agronomics accost many environmental and social concerns, simply it offers innovative and economically viable opportunities for growers, laborers, consumers, policymakers and many others in the unabridged food system.

This page is an effort to identify the ideas, practices and policies that institute our concept of sustainable agronomics. We exercise so for two reasons: 1) to analyze the research agenda and priorities of our programme, and 2) to advise to others practical steps that may be advisable for them in moving toward sustainable agriculture. Because the concept of sustainable agronomics is however evolving, we intend this page not as a definitive or final argument, just as an invitation to continue the dialogue

- What is Sustainable Agronomics?

-

A multifariousness of philosophies, policies and practices have contributed to these goals. People in many different capacities, from farmers to consumers, take shared this vision and contributed to it.

A multifariousness of philosophies, policies and practices have contributed to these goals. People in many different capacities, from farmers to consumers, take shared this vision and contributed to it.Despite the variety of people and perspectives, the following themes commonly weave through definitions of sustainable agriculture:

Sustainability rests on the principle that nosotros must meet the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their ain needs.

Therefore,stewardship of both natural and human resource is of prime number importance. Stewardship of human resource includes consideration of social responsibilities such equally working and living conditions of laborers, the needs of rural communities, and consumer health and safety both in the present and the future. Stewardship of land and natural resources involves maintaining or enhancing this vital resource base of operations for the long term.Asystems perspective is essential to agreement sustainability.

The system is envisioned in its broadest sense, from the individual subcontract, to the local ecosystem,and to communities afflicted by this farming system both locally and globally. An accent on the system allows a larger and more than thorough view of the consequences of farming practices on both human being communities and the environment. A systems approach gives us the tools to explore the interconnections between farming and other aspects of our environment.Anybody plays a role in creating a sustainable food system.

A systems approach too impliesinterdisciplinary efforts in inquiry and education.

A systems approach too impliesinterdisciplinary efforts in inquiry and education.

This requires not only the input of researchers from various disciplines, but also farmers, farmworkers, consumers, policymakers and others.Making the transition to sustainable agriculture is a process.

For farmers, the transition to sustainable agriculture normally requires a series of small, realistic steps. Family economics and personal goals influence how fast or how far participants can go in the transition. It is important to realize that each pocket-sized conclusion can make a divergence and contribute to advancing the entire system further on the "sustainable agriculture continuum." The key to moving forward is the volition to take the next step.Finally, it is important to point out thatreaching toward the goal of sustainable agriculture is the responsibleness of all participants in the system, including farmers, laborers, policymakers, researchers, retailers, and consumers. Each group has its own office to play, its ain unique contribution to make to strengthen the sustainable agriculture community.

The remainder of this page considers specific strategies for realizing these broad themes or goals. The strategies are grouped co-ordinate to iii separate though related areas of business organisation:Farming and Natural Resources,Plant and Creature Production Practices, and theEconomic, Social and Political Context. They correspond a range of potential ideas for individuals committed to interpreting the vision of sustainable agronomics within their own circumstances.

- Farming and Natural Resources

-

When the production of food and fiber degrades the natural resource base, the ability of future generations to produce and flourish decreases. The reject of aboriginal civilizations in Mesopotamia, the Mediterranean region, Pre-Columbian southwest U.S. and Central America is believed to take been strongly influenced by natural resource deposition from non-sustainable farming and forestry practices.

H2o

H2o Water is the primary resource that has helped agriculture and society to prosper, and information technology has been a major limiting factor when mismanaged.

Water supply and use. In California, an extensive water storage and transfer system has been established which has allowed crop production to aggrandize to very barren regions. In drought years, express surface water supplies accept prompted overdraft of groundwater and consequent intrusion of common salt water, or permanent collapse of aquifers. Periodic droughts, some lasting up to 50 years, accept occurred in California.

Several steps should be taken to develop drought-resistant farming systems fifty-fifty in "normal" years, including both policy and management deportment:

one) improvingh2o conservation and storage measures,

2) providing incentives for choice of drought-tolerant crop species,

3) usingreduced-volume irrigation systems,

4) managing crops to reduce water loss, or

v) not planting at all.

H2o quality.The near of import bug related to water quality involve salinization and contamination of ground and surface waters past pesticides, nitrates and selenium. Salinity has go a problem wherever water of even relatively low salt content is used on shallow soils in arid regions and/or where the water table is most the root zone of crops. Tile drainage can remove the water and salts, only the disposal of the salts and other contaminants may negatively affect the surroundings depending upon where they are deposited. Temporary solutions include the utilise of common salt-tolerant crops, depression-volume irrigation, and various management techniques to minimize the effects of salts on crops. In the long-term, some farmland may need to be removed from production or converted to other uses. Other uses include conversion of row crop country to production of drought-tolerant forages, the restoration of wild fauna habitat or the use of agroforestry to minimize the impacts of salinity and loftier water tables. Pesticide and nitrate contamination of water tin exist reduced using many of the practices discussed later in thePlant Production Practices andAnimal Production Practices sections.

Wildlife. Another way in which agriculture affects water resources is through the destruction of riparian habitats within watersheds. The conversion of wild habitat to agricultural state reduces fish and wildlife through erosion and sedimentation, the furnishings of pesticides, removal of riparian plants, and the diversion of water. The institute diversity in and around both riparian and agricultural areas should be maintained in lodge to support a variety of wildlife. This diversity volition heighten natural ecosystems and could aid in agricultural pest management.

Free energy

Free energyModern agriculture is heavily dependent on non-renewable energy sources, especially petroleum. The continued use of these energy sources cannot be sustained indefinitely, yet to abruptly carelessness our reliance on them would be economically catastrophic. Even so, a sudden cutoff in free energy supply would be equally confusing. In sustainable agricultural systems, there is reduced reliance on non-renewable free energy sources and a commutation of renewable sources or labor to the extent that is economically feasible.

Air

AirMany agronomical activities bear upon air quality. These include fume from agronomical burning; grit from tillage, traffic and harvest; pesticide drift from spraying; and nitrous oxide emissions from the use of nitrogen fertilizer. Options to improve air quality include:

- incorporating crop residue into the soil

- using appropriate levels of cultivation

- and planting air current breaks, cover crops or strips of native perennial grasses to reduce grit. Soil

SoilSoil erosion continues to be a serious threat to our connected power to produce adequate food. Numerous practices accept been adult to keep soil in place, which include:

- reducing or eliminating tillage

- managing irrigation to reduce runoff

- and keeping the soil covered with plants or mulch.Enhancement of soil quality is discussed in the next department.

- Constitute Production Practices

-

Sustainable product practices involve a variety of approaches. Specific strategies must have into account topography, soil characteristics, climate, pests, local availability of inputs and the private grower'south goals.

Despite the site-specific and individual nature of sustainable agronomics, several general principles can be applied to assistance growers select appropriate management practices:

- Selection of species and varieties that are well suited to the site and to weather on the farm;

- Diversification of crops (including livestock) and cultural practices to heighten the biological and economical stability of the farm;

- Direction of the soil to enhance and protect soil quality;

- Efficient and humane employ of inputs; and

- Consideration of farmers' goals and lifestyle choices.Selection of site, species and variety

Preventive strategies, adopted early, can reduce inputs and assist found a sustainable product system. When possible, pest-resistant crops should be selected which are tolerant of existing soil or site conditions. When site selection is an option, factors such as soil type and depth, previous crop history, and location (e.grand. climate, topography) should be taken into business relationship before planting.

Variety

Diversified farms are usually more economically and ecologically resilient. While monoculture farming has advantages in terms of efficiency and ease of management, the loss of the crop in any one year could put a farm out of business and/or seriously disrupt the stability of a community dependent on that ingather. Past growing a diverseness of crops, farmers spread economical risk and are less susceptible to the radical price fluctuations associated with changes in supply and demand.

Properly managed, diverseness tin also buffer a subcontract in a biological sense. For example, in annual cropping systems,crop rotation can be used to suppress weeds, pathogens and insect pests. Also, cover crops can have stabilizing effects on the agroecosystem past holding soil and nutrients in place, conserving soil wet with mowed or standing dead mulches, and past increasing the water infiltration rate and soil water holding capacity.Comprehend crops in orchards and vineyards can buffer the system confronting pest infestations by increasing beneficial arthropod populations and can therefore reduce the need for chemical inputs. Using a variety of cover crops is as well important in guild to protect against the failure of a particular species to grow and to attract and sustain a wide range of beneficial arthropods.

Optimum diversity may be obtained by integrating both crops and livestock in the aforementioned farming operation. This was the mutual practice for centuries until the mid-1900s when technology, government policy and economic science compelled farms to become more specialized. Mixed crop and livestock operations have several advantages. Showtime, growing row crops only on more level land and pasture or forages on steeper slopes will reduce soil erosion. Second, pasture and forage crops in rotation heighten soil quality and reduce erosion; livestock manure, in turn, contributes to soil fertility. Third, livestock can buffer the negative impacts of low rainfall periods by consuming ingather rest that in "plant only" systems would have been considered ingather failures. Finally, feeding and marketing are flexible in animal product systems. This can assistance cushion farmers against trade and price fluctuations and, in conjunction with cropping operations, make more efficient apply of farm labor.

Soil management

A common philosophy among sustainable agriculture practitioners is that a "healthy" soil is a key component of sustainability; that is, a healthy soil will produce good for you crop plants that take optimum vigor and are less susceptible to pests. While many crops accept fundamental pests that attack even the healthiest of plants, proper soil, water and nutrient direction can help preclude some pest issues brought on by crop stress or nutrient imbalance. Furthermore, crop management systems that impair soil quality often result in greater inputs of water, nutrients, pesticides, and/or energy for tillage to maintain yields.

In sustainable systems, the soil is viewed as a fragile and living medium that must be protected and nurtured to ensure its long-term productivity and stability. Methods to protect and enhance the productivity of the soil include:

- using cover crops, compost and/or manures

- reducing tillage

- fugitive traffic on wet soils

- maintaining soil cover with plants and/or mulchesConditions in virtually California soils (warm, irrigated, and tilled) exercise non favor the buildup of organic affair. Regular additions of organic matter or the use of cover crops can increase soil aggregate stability, soil tilth, and diversity of soil microbial life.

Efficient apply of inputs

Many inputs and practices used by conventional farmers are also used in sustainable agriculture. Sustainable farmers, still, maximize reliance on natural, renewable, and on-farm inputs. Equally of import are the environmental, social, and economic impacts of a detail strategy. Converting to sustainable practices does non mean uncomplicated input substitution. Oftentimes, information technology substitutes enhanced direction and scientific knowledge for conventional inputs, especially chemical inputs that impairment the environs on farms and in rural communities. The goal is to develop efficient, biological systems which do not need loftier levels of material inputs.

Growers oftentimes ask if synthetic chemicals are appropriate in a sustainable farming system. Sustainable approaches are those that are the to the lowest degree toxic and least energy intensive, and yet maintain productivity and profitability. Preventive strategies and other alternatives should be employed before using chemical inputs from whatsoever source. However, there may exist situations where the apply of synthetic chemicals would be more "sustainable" than a strictly non-chemical arroyo or an approach using toxic "organic" chemicals. For example, one grape grower switched from cultivation to a few applications of a wide spectrum contact herbicide in the vine row. This approach may utilize less free energy and may compact the soil less than numerous passes with a cultivator or mower.

Consideration of farmer goals and lifestyle choices

Management decisions should reflect not only environmental and broad social considerations, but also individual goals and lifestyle choices. For example, adoption of some technologies or practices that hope profitability may besides require such intensive management that one'southward lifestyle actually deteriorates. Management decisions that promote sustainability, nourish the surround, the community and the individual.

- Brute Product Practices

-

In the early part of this century, most farms integrated both crop and livestock operations. Indeed, the ii were highly complementary both biologically and economically. The current film has changed quite drastically since then. Ingather and brute producers now are all the same dependent on one another to some degree, but the integration now most usually takes place at a higher level--between farmers, through intermediaries, rather thanwithin the farm itself. This is the result of a tendency toward separation and specialization of crop and brute production systems. Despite this trend, at that place are still many farmers, particularly in the Midwest and Northeastern U.Southward. that integrate crop and brute systems--either on dairy farms, or with range cattle, sheep or pig operations.

Even with the growing specialization of livestock and crop producers, many of the principles outlined in the crop production department apply to both groups. The actual management practices will, of class, be quite different. Some of the specific points that livestock producers need to address are listed below.

Management Planning

Including livestock in the farming system increases the complication of biological and economic relationships. The mobility of the stock, daily feeding, health concerns, convenance operations, seasonal feed and provender sources, and complex marketing are sources of this complexity. Therefore, a successful ranch programme should include enterprise calendars of operations, stock flows, provender flows, labor needs, herd production records and land use plans to give the manager control and a ways of monitoring progress toward goals.

Beast Selection

The animal enterprise must be appropriate for the subcontract or ranch resources. Farm capabilities and constraints such as feed and provender sources, landscape, climate and skill of the manager must be considered in selecting which animals to produce. For example, ruminant animals tin can be raised on a diverseness of feed sources including range and pasture, cultivated provender, cover crops, shrubs, weeds, and ingather residues. There is a wide range of breeds available in each of the major ruminant species, i.eastward., cattle, sheep and goats. Hardier breeds that, in general, have lower growth and milk production potential, are better adapted to less favorable environments with sparse or highly seasonal forage growth.

Animal nutrition

Feed costs are the largest single variable price in whatever livestock functioning. While most of the feed may come from other enterprises on the ranch, some purchased feed is commonly imported from off the farm. Feed costs can be kept to a minimum by monitoring animal condition and performance and understanding seasonal variations in feed and forage quality on the farm. Determining the optimal use of farm-generated by-products is an important claiming of diversified farming.

Reproduction

Employ of quality germplasm to amend herd functioning is another cardinal to sustainability. In combination with skilful genetic stock, adapting the reproduction season to fit the climate and sources of feed and forage reduce wellness bug and feed costs.

Herd Health

Beast wellness greatly influences reproductive success and weight gains, ii key aspects of successful livestock production. Unhealthy stock waste feed and require additional labor. A herd wellness plan is disquisitional to sustainable livestock product.

Grazing Management

Well-nigh adverse environmental impacts associated with grazing can be prevented or mitigated with proper grazing management. First, the number of stock per unit of measurement area (stocking rate) must be right for the landscape and the forage sources. There will need to be compromises between the convenience of tilling large, unfenced fields and the fencing needs of livestock operations. Apply of modern, temporary fencing may provide one practical solution to this dilemma. Second, the long term carrying capacity and the stocking charge per unit must have into account brusque and long-term droughts. Especially in Mediterranean climates such as in California, properly managed grazing significantly reduces burn hazards by reducing fuel build-upwards in grasslands and brushlands. Finally, the manager must achieve sufficient command to reduce overuse in some areas while other areas go unused. Prolonged concentration of stock that results in permanent loss of vegetative embrace on uplands or in riparian zones should exist avoided. However, small-scale scale loss of vegetative cover effectually water or feed troughs may be tolerated if surrounding vegetative cover is adequate.

Confined Livestock Production

Creature health and waste material direction are fundamental issues in confined livestock operations. The moral and ethical debate taking place today regarding animal welfare is particularly intense for confined livestock production systems. The issues raised in this debate need to be addressed.

Confinement livestock production is increasingly a source of surface and footing water pollutants, particularly where there are large numbers of animals per unit expanse. Expensive waste management facilities are now a necessary cost of confined production systems. Waste material is a problem of near all operations and must be managed with respect to both the environment and the quality of life in nearby communities. Livestock product systems that disperse stock in pastures so the wastes are not concentrated and do not overwhelm natural nutrient cycling processes have become a field of study of renewed involvement.

- The Economical, Social & Political Context

-

In addition to strategies for preserving natural resources and changing production practices, sustainable agronomics requires a commitment to changing public policies, economic institutions, and social values. Strategies for modify must take into account the circuitous, reciprocal and always-irresolute relationship betwixt agronomical product and the broader society.

The "food system" extends far across the farm and involves the interaction of individuals and institutions with contrasting and often competing goals including farmers, researchers, input suppliers, farmworkers, unions, farm advisors, processors, retailers, consumers, and policymakers. Relationships among these actors shift over fourth dimension equally new technologies spawn economic, social and political changes.

A wide diversity of strategies and approaches are necessary to create a more sustainable food system. These volition range from specific and concentrated efforts to change specific policies or practices, to the longer-term tasks of reforming key institutions, rethinking economic priorities, and challenging widely-held social values. Areas of business organization where change is most needed include the post-obit:

Food and agricultural policy

Existing federal, state and local government policies often impede the goals of sustainable agronomics. New policies are needed to simultaneously promote environmental health, economic profitability, and social and economic equity. For example, commodity and price support programs could be restructured to permit farmers to realize the total benefits of the productivity gains made possible through culling practices. Tax and credit policies could be modified to encourage a diverse and decentralized system of family farms rather than corporate concentration and absentee ownership. Government and state grant university research policies could exist modified to emphasize the evolution of sustainable alternatives. Marketing orders and corrective standards could exist amended to encourage reduced pesticide use. Coalitions must be created to address these policy concerns at the local, regional, and national level.

Country employ

Conversion of agricultural land to urban uses is a particular business organization in California, as rapid growth and escalating land values threaten farming on prime soils. Existing farmland conversion patterns often discourage farmers from adopting sustainable practices and a long-term perspective on the value of state. At the aforementioned time, the shut proximity of newly developed residential areas to farms is increasing the public demand for environmentally condom farming practices. Comprehensive new policies to protect prime soils and regulate development are needed, particularly in California'due south Central Valley. By helping farmers to adopt practices that reduce chemical use and conserve scarce resources, sustainable agriculture inquiry and didactics can play a fundamental role in building public support for agricultural land preservation. Educating country use planners and determination-makers most sustainable agronomics is an important priority.

Labor

In California, the conditions of agricultural labor are more often than not far beneath accepted social standards and legal protections in other forms of employment. Policies and programs are needed to address this trouble, working toward socially simply and condom employment that provides adequate wages, working atmospheric condition, health benefits, and chances for economic stability. The needs of migrant labor for year-around employment and adequate housing are a particularly crucial trouble needing immediate attention. To be more than sustainable over the long-term, labor must be acknowledged and supported by regime policies, recognized as of import constituents of land grant universities, and carefully considered when assessing the impacts of new technologies and practices.

Rural Customs Evolution

Rural communities in California are currently characterized by economic and environmental deterioration. Many are amidst the poorest locations in the nation. The reasons for the decline are complex, but changes in farm structure have played a significant role. Sustainable agriculture presents an opportunity to rethink the importance of family farms and rural communities. Economic development policies are needed that encourage more diversified agricultural production on family farms as a foundation for good for you economies in rural communities. In combination with other strategies, sustainable agronomics practices and policies can help foster community institutions that come across employment, educational, health, cultural and spiritual needs.

Consumers and the Food System

Consumers can play a disquisitional function in creating a sustainable nutrient system. Through their purchases, they transport strong messages to producers, retailers and others in the system about what they think is of import. Food cost and nutritional quality have e'er influenced consumer choices. The challenge now is to find strategies that broaden consumer perspectives, so that ecology quality, resource employ, and social disinterestedness issues are as well considered in shopping decisions. At the same time, new policies and institutions must exist created to enable producers using sustainable practices to market place their goods to a wider public. Coalitions organized around improving the food arrangement are one specific method of creating a dialogue amid consumers, retailers, producers and others. These coalitions or other public forums can be important vehicles for clarifying problems, suggesting new policies, increasing common trust, and encouraging a long-term view of food production, distribution and consumption.

Contributors: Written by Gail Feenstra, Author; Chuck Ingels, Perennial Cropping Systems Analyst; and David Campbell, Economic and Public Policy Analyst with contributions from David Chaney, Melvin R. George, Eric Bradford, the staff and advisory committees of the UC Sustainable Agriculture Research and Education Program.

How to cite this page

UC Sustainable Agriculture Research and Education Programme. 2021. "What is Sustainable Agronomics?" UC Agriculture and Natural Resources. <https://sarep.ucdavis.edu/sustainable-ag>

This page was last updated August 3, 2021.

Farm Typology And Sustainable Agriculture: Does Size Matter?,

Source: https://sarep.ucdavis.edu/sustainable-ag

Posted by: brownnepre1992.blogspot.com

0 Response to "Farm Typology And Sustainable Agriculture: Does Size Matter?"

Post a Comment